⛲ Humorism or fluid mechanics in ancient medicine

Roses are red, blood is hot, and phlegm, in all its cold, moist glory, reigns supreme.

What better way to kick off this newsletter than to step together into the world of humor, a delightful ancient Greek pastime of turning bodily fluids into profound ponderings.

🏛️ Ancient beginnings: Hippocrates and the Four Humors

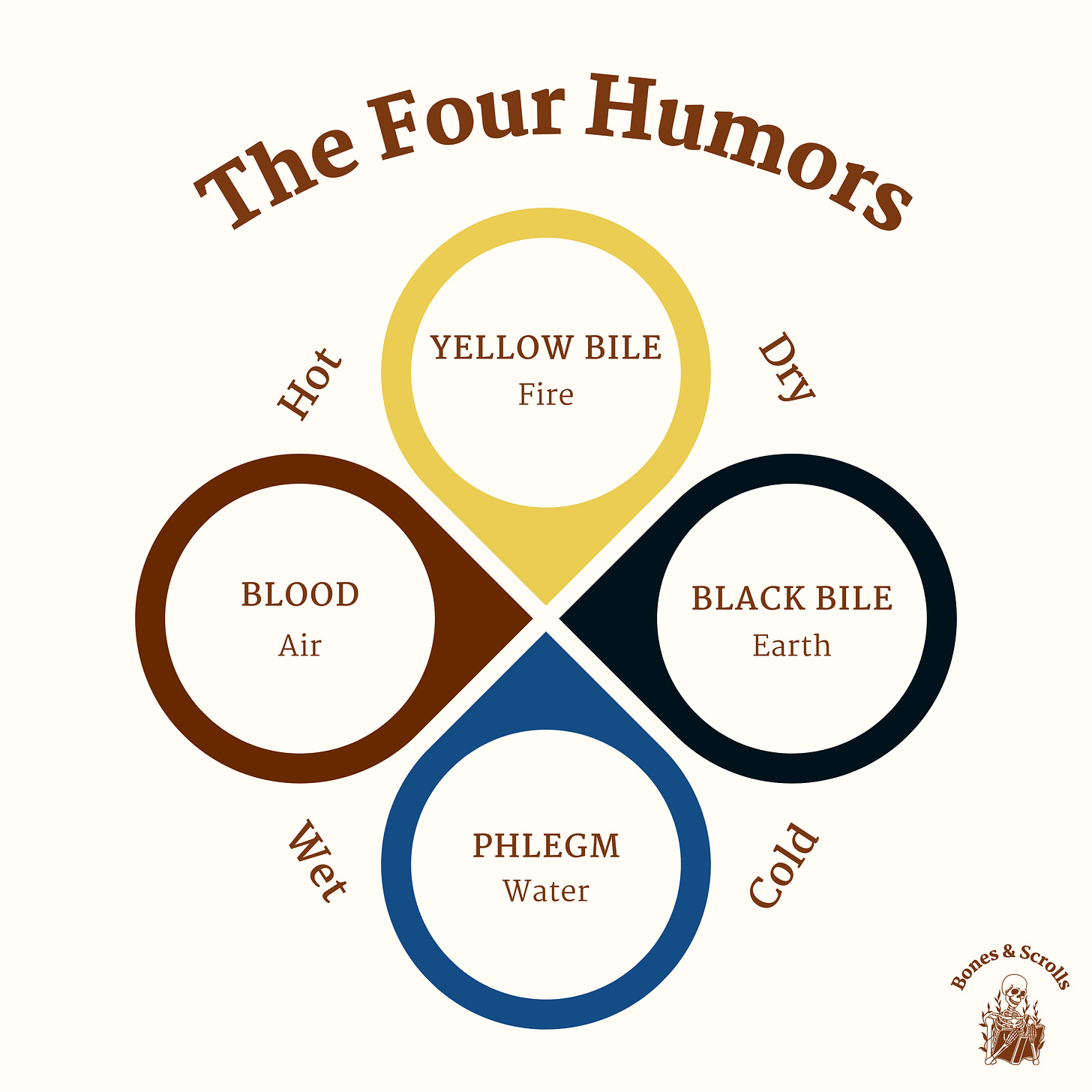

Our story begins with none other than the OG of medicine, the granddaddy of health, Hippocrates, who, in his prime, rocked a toga like no one else. Hippocrates, the "Father of Western Medicine," argued that the key to well-being lay in the balance of four essential fluids—blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile1. Each humor had its distinct personality: blood was warm and moist, phlegm cold and moist, yellow bile warm and dry, and black bile – you guessed it - cold and dry and well, a buzzkill.

⚖️ Balancing act: humors and health

Hang onto your laurel wreaths, because the plot thickens with the entrance of Roman physician Galen. Galen took the Hippocratic framework and ran with it, expanding upon the concept of balancing the four humors for optimal health2.

In Galenic humoral theory, each humor is associated with a vital organ: blood with the heart, phlegm with the brain, yellow bile with the liver and black bile with the spleen. Each humor embodies the qualities of hot, cold, wet and dry, and symbolizes the elements of fire, air, water and earth3.

Galen intricately linked humors to temperament and even physical traits, arguing that maintaining this fluidic harmony (eucrasia) was the key to a hale and hearty existence. But, heaven forbid, if the scales tipped in favor of one or the other, woe unto you, for imbalance (dyscrasia) begat illness. Black bile overdose? Cue the melancholy playlist. Yellow bile surplus? Get ready for some crankiness and a feverish fiesta.

Galen's toolbox included remedies such as bloodletting and dietary modifications, all designed to reinstate that ever-elusive equilibrium of humors. His influence on the field of medicine endured for centuries, significantly shaping the trajectory of Western medical practices and beliefs4.

🖋 Evolution and transmission

Humoral theory didn't merely linger like an unwelcome flu bug; it embarked on a global journey, finding its way into the realm of Islamic medicine, courtesy of scholars such as Avicenna who found its allure irresistible5. Later, it circled back to the Christian West through Latin translations of Arabic texts, leaving its mark on the evolution of medieval European medicine6.

🎭 Chaucer's "Doctor of Physic" and Shakespearian phlegm

In the Middle Ages, humoral theory was the belle of the ball. It waltzed into literary works like Chaucer's "The Canterbury Tales," where we meet a doctor who couldn't get enough of that humor7. Shakespeare, too, had a thing for the humors and filled his scripts with characters embodying them8. Falstaff, for instance, was the poster child for the phlegmatic temperament, which in his case, meant he was unattractive and perennially under the weather. Turns out that Grey's Anatomy is no match for Shakespearian medical dramas.

Adolf Schrödter: Falstaff and his page

🕯 Continued impact on medicine

But even as medicine moved forward, humoral theory didn't check out. Well into the 19th century, bloodletting parties were all the rage, and the concept of miasmatic theory, linking diseases to the environment, held sway. These theories hung on like that pesky cough you can't shake before finally bowing to the rise of germ theory.

And while we no longer dabble in the alchemy of humoral medicine, we've kept the lingo. Words like "melancholic," "sanguine," "phlegmatic," and "bilious" still trip off our tongues when describing personality quirks.

So the next time someone calls you "melancholic", you can smile knowingly and say: "It's just my black bile acting up". What a comeback.

Bynum, W. (2008). Medicine at the bedside. In The history of medicine a very short introduction, Oxford University Press.

Bynum, W. (2008). Medicine at the bedside. In The history of medicine a very short introduction, Oxford University Press.

Hollerbach, T. (2023). Sanctorius’s galenism. Sanctorius Sanctorius and the Origins of Health Measurement, 35–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-30118-6_3

Bynum, W. (2008). Medicine at the bedside. In The history of medicine a very short introduction, Oxford University Press.

Radden, J. (2002). Black Bile and Melancholia. The Nature of Melancholy, 75–78. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195151657.003.0005

Bynum, W. (2008). Medicine at the bedside. In The history of medicine a very short introduction, Oxford University Press.

Rawcliffe, C. (2014). The doctor of physic. Historians on Chaucer, 297–318. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199689545.003.0017

Ekström, N. (n.d.). Shakespeare and the four Humours. Wellcome Collection. https://wellcomecollection.org/articles/W-MM-xUAAAinxgs3